ESIL Reflection Searching for the Eastern Carelia Principle

PDF Version

PDF Version

Vol 8, Issue 1

Editorial board: Samantha Besson, Jean d’Aspremont (Editor-in-Chief), Jan Klabbers and Christian Tams

Philip Burton

Research Fellow, Manchester International Law Centre (MILC)

University of Manchester

State consent has long been recognised to be an essential condition for the resolution of disputes by international bodies. There have been a range of unsuccessful attempts to introduce compulsory adjudication into international law, most notably during the drafting of the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice (the ‘Permanent Court’ and the ‘PCIJ’).[1] However, the decision to vest the Permanent Court with an advisory jurisdiction, which would be triggered by a request from an international organization rather than an expression of state consent, raised the prospect (or spectre) of ‘backdoor’ compulsory adjudication. Ever since, states, judges and scholars have struggled to square the consensual basis of international adjudication in general, with the particular nature of the advisory jurisdiction.

This question lay at the heart of one of the most venerable and enigmatic advisory opinions in international law: the Eastern Carelia opinion.[2] In the Eastern Carelia opinion the Permanent Court refused to render an advisory opinion on a dispute where one of the parties rejected any form of international involvement. This refusal gave rise to what is generally referred to as the Eastern Carelia principle, which is orthodoxly understood as meaning that state consent is a precondition for the exercise of the advisory jurisdiction in bilateral disputes. Based at once on sovereignty of states and the particular architecture of the interbellum institutions, the precedential weight of the opinion was almost immediately cast in doubt. Nevertheless, the Eastern Carelia principle has been repeatedly invoked before, and endorsed by, the International Court of Justice (the ‘International Court’ and the ‘ICJ’). Despite the respect (or lip-service) that the International Court has paid to the principle, it has never been directly applied. Instead the principle has been distinguished on increasingly broad grounds. This repeated willingness of the International Court to render advisory opinions in situations that directly affected states regard as bilateral has led to periodic enquiries into the ‘death’ of the principle, or that it lives merely as “a rhetorical, rather than an operative, principle.”[3]

This question also lies at the heart of the General Assembly’s request for an advisory opinion on the ‘Legal consequences of the separation of Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965’.[4] Yet again, the Court is faced with a request which appears to stretch the elasticity of the principle to breaking point. The United Kingdom insists that the dispute between itself and Mauritius over the Chagos Archipelago is ‘bilateral’ and should be resolved through negotiations. As the US representative succinctly put it, during the debate in the General Assembly, “The advisory function of the International Court of Justice was not intended to settle disputes between States.”[5] Should the International Court decide to render an advisory opinion, its decision will doubtless lead to many proclaiming the decision to be the final nail in the coffin of the principle.

This reflection does not presume to judge the desirability of whether the International Court should render an advisory opinion on the lawfulness of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago. Rather, it is intended to provide a retrospective of this most paradoxical of principles. In doing so, I argue that the Eastern Carelia principle is better conceived as a self-empowering doctrine, which enables the Court to decline requests for advisory opinions on a range of grounds, rather than one which necessarily prevents the Court from hearing bilateral disputes. This reflection begins by providing a brief analysis of the Eastern Carelia opinion. As noted above, the opinion was grounded both in the specific institutional arrangement of the interbellum and upon fundamental principles of international law. The second part therefore examines how the opinion has been received by the present Court. In the final section, I provide a brief survey of the lie of the land with respect to the present dispute and present a few tentative thoughts about how the ‘Eastern Carelia principle’ ought to be conceived of in future cases: namely, that we should understand the Court to be empowered to exercise discretion, rather than bound to reject requests concerning bilateral disputes in the absence of state consent.

1. The Eastern Carelia Opinion

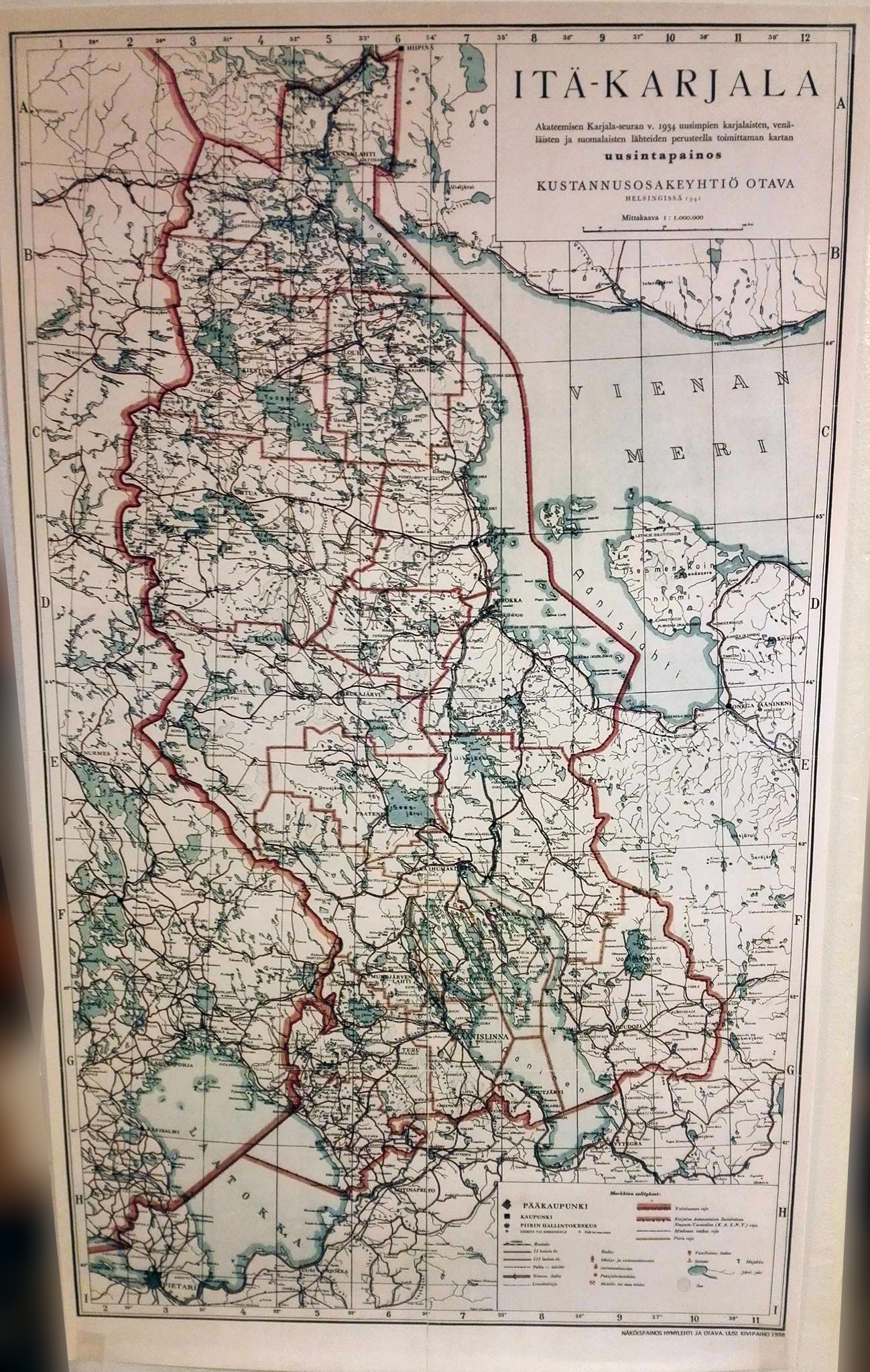

The original opinion arose from a dispute between Finland and Russia regarding the status of Eastern Carelia, a Russian province adjacent to Finland. The Council of the League of Nations was willing to help, but unable to initiate its dispute resolution procedures without Russia’s consent. Consequently, Finland proposed that the Council should request an advisory opinion. The Council eagerly accepted Finland’s proposal, with the Rapporteur, M. Salandra, arguing that ‘the Council undoubtedly has the right to refer this question to the Court’ as there was ‘no restriction limiting the Council’s right to ask advisory opinions on any dispute or point which it desires to submit to the Court.’[6] Salandra recognised that Soviet Russia’s involvement required ‘special attention’ as the Soviet regime had not yet been recognised de jure by other states and, also, on several occasions, had shown its ‘hostility to the League of Nations.’[7] In order to side-step the absence of Russian consent, Salandra asserted that ‘there will be no “parties” in the strict sense of the word.’[8]

Proceedings were opened by Permanent Court requesting the Finnish agent to submit pleadings regarding the Court’s competence to hear the case.[9] Again, Russia reiterated its unwillingness to involve third parties in the dispute.[10] At the outset of the opinion, the Court observed that there had ‘been some discussion as to whether questions for an advisory opinion, if they relate to matters which form the subject of a pending dispute between nations, should be put to the Court without the consent of the parties.’[11] However, the Permanent Court avoided giving a direct answer to this question because there were other reasons to reject the request.

Chief among these was the competency of the Council to refer the matter to the Court. The Court observed that it was called upon to give its views ‘on an actual dispute between Finland and Russia.’[12] According to Article 17 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, the Council could only exercise its functions with regards to non-member states if they accepted Council intervention. Furthermore, Article 17 merely reflected the ‘fundamental principle’ of ‘the independence of States.’[13] It was ‘well established’ that ‘no State can, without its consent, be compelled to submit its disputes with other States’ to any form of pacific settlement.[14] Russia’s rejection of League involvement meant the League was incompetent to refer the matter to the Court and the Court, therefore, could not render an advisory opinion.[15]

The Court did not pronounce directly on the specific question of whether or not state consent was a precondition for the exercise of its advisory jurisdiction. However, the foregoing certainly appears to imply an affirmative answer. The Court stated that the requirement of state consent for third party settlement was a positive rule, Article 17, but also a fundamental, or constitutional, rule of the international order. If this is the case, ought it be read into provisions which are silent in this regard, for instance Article 14? The PCIJ appeared to suggest as much, later in the opinion, when it stated that it was:

… aware of the fact that it is not requested to decide a dispute, but to give an advisory opinion. This circumstance, however, does not essentially modify the above considerations. The question put to the Court is not one of abstract law, but concerns directly the main point of the controversy between Finland and Russia… Answering the question would be substantially equivalent to deciding the dispute between the parties.[16]

Taken as a whole, the opinion is deeply ambiguous regarding the necessity for state consent with regards to the advisory jurisdiction. The Court stated at the outset that it did not intend to pronounce on the matter, but the substance of its opinion creates a strong implication that consent was indeed necessary. Recent scholarship suggests that this central ambiguity was not an accident, but rather reflected the fact that the PCIJ was divided. According to Spiermann, ‘[t]here can hardly be any doubt’ that judge Moore’s supported the broadest reading of the opinion, and that this view was shared by Judge Anzilotti and perhaps Judge Finlay.[17] However, this view was not universal. Moore later observed that ‘the Court indicated that its conclusion might have been different if Russia had been a Member of the League.’[18]

Outside of the Court, the opinion was met with a decidedly mixed reaction. The Council accepted the opinion, but, in doing so, sought to limit the scope of the principle to the facts of the case and minimise its precedential force.[19] Despite the intention of temperance, Judge Moore considered the Council’s response to be a ‘scarcely veiled admonition levelled at the Court.’[20] This ‘temperate’ – in the Council’s eyes[21] – ‘admonition’ would have profound consequences, particularly with respect to the mooted US accession to the Court’s Statute. Moore – hitherto a staunch proponent of US accession – went on to play an important role in the drafting of the infamous fifth reservation regarding the US accession to the Court’s Statute. This reservation stated that: ‘That the Court shall not […] entertain any request for an advisory opinion touching any dispute or question in which the United States has or claims an interest.’[22] Nevertheless, the Conference of the Parties, organised to discuss the terms of US accession to the Statute, appeared to support the wider reading of the Eastern Carelia opinion and stated that it considered the precedent sufficient to address the fifth reservation.[23]

It is important to distinguish between the two significant aspects of this opinion. First, and foremost, the opinion was constitutive of the powers of the Court, in that the Court asserted its ability to reject requests for advisory opinions. During the drafting of the Statute there had been an unresolved conflict as to whether the Court ought to function as a ‘Court of Justice’ or a legal advisor while operating in its advisory mode: the Eastern Carelia opinion represented the triumph of the vision of the Court as a Court of Justice, enhancing its autonomy from the League and judicial character.[24] Secondly, the opinion endorsed the ‘constitutional’ rule that state consent was a precondition for third party settlement, however, it did so in an ambiguous fashion which raised many questions regarding the precise content of the principle. Crucially, the question of the applicability of this principle to the advisory jurisdiction was left open.

2. The Eastern Carelia Principle Outwith the interbellum Institutional Architecture

The Eastern Carelia opinion was grounded both upon fundamental principles derived from the independence of states and the particular institutional context of the interbellum. It was, therefore, an open question whether the principle ought to survive the ‘constitutional and organic’ transformations that the adoption of the UN Charter ushered in.[25] The incorporation of the new Court within the UN’s structure; the use of majority voting and, after initial controversy, the rapid expansion of membership introduced new dynamics which any return to Eastern Carelia would need to accommodate. As membership would near universality, the majority voting of the General Assembly could be argued to provide a countervailing jurisdictional basis based on the ‘will of the international community’, rather than the will of states. The following section will briefly examine how the ICJ has applied the ‘Eastern Carelia principle,’ demonstrating that the Court has always endorsed the principle and brought a measure of clarity regarding its nature, but, simultaneously, has distinguished it in increasingly broad strokes.

While, during the interwar, requests for advisory opinions were adopted by unanimity, the turn to majority voting meant that objections, based on the Eastern Carelia principle, became regular. The earliest significant example of this arose in Interpretation of Peace Treaties, where various states invoked, or distinguished, the Eastern Carelia advisory opinion in their pleadings. The case concerned the refusal of three states (Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania) to appoint representatives to human rights commissions established under the peace treaties, meaning that the Commissions fell short of their quorum and were incapable of rendering decisions. The General Assembly essentially asked the Court whether there was any way in which the body could be rendered operational. The three states were not, at the time, members of the United Nations.

The Court dismissed the broadest interpretation of the Eastern Carelia principle, namely that state consent was a jurisdictional requirement for the performance of the advisory function. The argument that state consent was a necessary precondition for the advisory function demonstrated ‘a confusion between the principles governing contentious procedure and those which are applicable to Advisory Opinions.’[26] Consent was the basis of the contentious jurisdiction, however:

The situation is different in regard to advisory proceedings even where the Request for an Opinion relates to a legal question actually pending between States […] no State, whether a Member of the United Nations or not, can prevent the giving of an Advisory Opinion which the United Nations considers to be desirable in order to obtain enlightenment as to the course of action it should take. The Court’s Opinion is given not to the States, but to the organ which is entitled to request it; the reply of the Court, itself an “organ of the United Nations”, represents its participation in the activities of the Organization, and, in principle, should not be refused.[27]

Nevertheless, in certain circumstances, the Court was entitled to decline requests for advisory opinions.[28] While an absence of consent was irrelevant to the question of whether the Court possessed jurisdiction, it may render a request inadmissible. Consequently, the Court felt it necessary to distinguish the case at hand from Eastern Carelia because the request pertained to the operation of institutional mechanisms as opposed to the merits of the dispute.[29] Consequently, the Court found that ‘the sole object’ of the request was to ‘enlighten the General Assembly as to the opportunities which the procedure contained in the Peace Treaties may afford for putting an end to a situation which has been presented to it.’[30] Interpretation of Peace Treaties, therefore raised as many questions as it answered. On the one hand, the International Court’s discussion of the matter brought a measure of clarity regarding the nature of the Easter Carelia principle: State consent was not a jurisdictional requirement for a request for an advisory opinion, but its absence may render a request inadmissible. However, on the other hand, the International Court appeared to rest its decision on an unstable distinction between procedural and substantive questions.[31] Lastly, the appraisal of the applicability of the Eastern Carelia principle, protecting state sovereignty, had to be weighed against a countervailing principle regarding the International Court’s duty to cooperate with the other UN organs. This construction made it clear that the application of the Eastern Carelia principle was discretionary, the indication that a lack of consent was not the sole circumstance for refusing a request further enhanced this.

This present reflection does not lend itself to a detailed examination of the admissibility of requests for advisory opinions concerning bilateral disputes, although two clear patterns emerged. Firstly, the establishment of an institutional interest consistently trumped the protection of individual state interests. Secondly, the Court repeatedly hinted at limits to its discretion, only to transgress its self-imposed restraints in subsequent opinions. It is, nevertheless, worthwhile to examine the most recent interpretation of the Eastern Carelia opinion: The Wall advisory opinion. Israel had sought to have the request dismissed because it concerned ‘a contentious matter between Israel and Palestine, in respect of which Israel has not consented.’[32] Again, the ICJ stated that a lack of consent was no issue with regards to jurisdiction, but may present a bar to admissibility.[33] The Court began by staking out the institutional interest in the matter. In light of the UN’s competence with regard to peace and security, ‘the construction of the wall must be deemed to be directly of concern to the United Nations.’[34] Moreover, the UN had a special responsibility towards the Palestinian Question, with ‘its origin in the Mandate and the Partition Resolution.’[35]

The Court then proceeded to examine the specific circumstances of the request for an advisory opinion:

The object of the request before the Court is to obtain from the Court an opinion which the General Assembly deems of assistance to it for the proper exercise of its functions. The opinion is requested on a question which is of particularly acute concern to the United Nations, and one which is located in a much broader frame of reference than a bilateral dispute. In the circumstances, the Court does not consider that to give an opinion would have the effect of circumventing the principle of consent to judicial settlement, and the Court accordingly cannot, in the exercise of its discretion, decline to give an opinion on that ground.[36]

Lastly, and crucially, the majority found that the ‘Court cannot substitute its assessment of the usefulness of the opinion requested for that of the organ that seeks such opinion.’[37] The Court was merely to ‘determine in a comprehensive manner the legal consequences of the construction of the wall, while the General Assembly … may then draw conclusions from the Court’s findings.’[38] The Wall advisory opinion thus confirmed the post-war trend, emphasizing the constitutive aspects of the ‘Eastern Carelia principle’, while diluting the constitutional safeguard its earliest proponents intended. In doing so, it escaped the interwar debates over the content of the principle and established a wide margin of discretion for itself.

3. On the Horizon of International Adjudication

The arguments advanced within the General Assembly prior to the adoption of resolution 71/292, requesting the advisory opinion on the separation of the Chagos Archipelago, demonstrated that its opponents and proponents are already engaged in the struggle to frame the request. In the introductory speech, the Congolese representative sought to situate the dispute within the universal theme of decolonisation, a core responsibility of the UN which remains incomplete.[39] Consequently, the UN would benefit from the issuance of an advisory opinion from the ICJ on the legality of the severance of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritania. The Mauritanian representative added to this line of argument, stating that ‘Draft resolution A/71/L.73 is not a belated wake-up call from Mauritius, as suggested by some. It addresses colonialism and decolonization — a matter of interest to all Members and to the Organization as a whole.’[40] Moreover, ‘[b]ilateral talks seeking to address this issue simply are not a basis for denying multilateral interests in the case.’[41]

Unsurprisingly, the British delegate sought to refute and undermine this view, arguing that questions on the British Indian Ocean Territory have long been a bilateral matter between the United Kingdom and Mauritius.’[42] The British delegate continued:

…the fact that the General Assembly has not concerned itself with this matter for decades shows that today’s debate has been called for other reasons. Put simply, the request for an advisory opinion is an attempt by the Government of Mauritius to circumvent the vital principle that a State is not obliged to have its bilateral disputes submitted for judicial settlement without its consent.[43]

This view was supported by the US representative, who argued that the request for an advisory opinion was an attempt ‘to circumvent the Court’s lack of contentious jurisdiction over this purely bilateral matter.’[44]

The request for an advisory opinion on the legal consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius pushes the boundaries etched out in the ICJ’s previous opinions. The request undoubtedly pertains to the merits of the dispute, contra Interpretation of Peace Treaties; it clearly arose in the context of bilateral relations, contra Western Sahara; and it is apparent that the General Assembly had not taken especial interest in the matter, prior to the request, for around forty years contra The Wall. Paradoxically, however, the request and the corresponding requests in the foregoing opinions are united by the fact that, in each instance, the request appeared to transgress the limits previously sketched out by the Court.

Moreover, the ICJ has repeatedly expressed the mantra, most forcefully in The Wall, that the purpose of the advisory function is to provide advice to the organ requesting it and requests ‘in principle, should not be refused.’[45] The process of decolonisation is a central competence of the General Assembly and the GA adopted numerous resolutions criticising the secession as events unfolded. If the GA considers the request to be relevant, then the Court is precluded from second-guessing this decision. However, any attempt to ascertain the content of the Eastern Carelia principle is hampered, perhaps fatally, by the fact that the Court has never laid out a positive conception of that principle; instead it has merely, on a case-by-case basis, established exceptions which make no claim to exhaustiveness.

But perhaps the foregoing is to misconstrue the Eastern Carelia principle. Perhaps it is a categorical error to even be examining the principle with the aspiration of ascertaining its content. More than any conventional rule or principle, the Eastern Carelia principle is best understood as an assertion of a power, a reservation of discretion on the part of the Court. While, according to the orthodox interpretation, the Eastern Carelia principle is understood to be a rule, in reality it is best understood as staking out a margin of discretion for the Court to make context-dependent decisions. This is not to argue that there is no ‘constitutional’ content – in the sense of protecting the rights of states from unwarranted interference – remaining in the Eastern Carelia principle. This reflection is not intended to continue in the vein of articles prematurely declaring the demise of the principle. Instead, it is argued that greater emphasis ought to be placed on the constitutive elements of the principle, the authority it confers upon the Court and the nature of that authority.

Focusing solely on the ‘constitutional’ aspect of the principle is over-inclusive: it does not distinguish between the Court’s ability to decline and an obligation to decline. However, it is also under-inclusive insofar as the question of whether or not a dispute is bilateral does not exhaust the potential reasons for the ICJ to find a request inadmissible. Fundamentally, this discretion is not bounded by ‘rules’ but instead involves the weighing of competing imperatives, rather than the application of rules. In each instance, the ICJ must balance the rights flowing from the independence of states (and any other reasons to decline to render an opinion) with Court’s own duty to assist in the workings of the UN. If we are to draw a ‘line of best fit’ through prior decisions, it is not unreasonable to arrive at the conclusion that the Eastern Carelia principle is ‘dead.’ However, perhaps the more significant pattern has been the willingness of the Court to transgress its self-imposed boundaries. The reality is that the decision must be taken anew, each time. Seen from this perspective, this ambiguity is no longer the ‘problem’ of the Eastern Carelia principle, to be resolved through legal method, but is, instead, its central feature. The ambiguity hinders the effectiveness of the ‘Eastern Carelia principle as a constitutional safeguard but serves the constitutive function of empowering the Court.

Subjecting the Eastern Carelia opinion to critical analysis means that we can see that, in addition to the explicit legal considerations, the Court’s decision to reject the request was also animated by the broader political and institutional questions of the day, in particular, US accession and the desire to secure the Court’s independence from the ‘political’ League. Similarly, the context in which the present Court decides upon the admissibility of the General Assembly’s request will not be limited to the dispute over the Chagos Archipelago but will encompass far wider considerations. This decision will be animated by the Court’s underlying assumptions about the international order and the role of the Court within it. As much as the Court may seek to frame its decisions on admissibility in legalistic reasoning, this question cannot be resolved through a legal epistemology. There can be no final synthesis of what the Eastern Carelia principle ‘means’, because, in order to play its function, it must be open to contestation.

Cite as: Philip Burton, ‘Searching for the Eastern Carelia Principle’, ESIL Reflections 8:1 (2019).

[1] See, generally, Spiermann, O., 2003. ‘Who Attempts Too Much Does Nothing Well’: the 1920 Advisory Committee of Jurists and the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice. The British Year Book of International Law, 73(1), p.187.

[2] The Status of Eastern Carelia, advisory opinion, PCIJ Series B, No. 5 (‘Eastern Carelia’).

[3] Pomerance, M., 2005. The ICJ’s Advisory Jurisdiction and the Crumbling Wall between the Political and the Judicial. American Journal of International Law, 99(1), pp.26-42. p. 30.

[4] United Nations General Assembly A/RES/71/292.

[5] A/71/PV.88, p. 13.

[6] Report by M. Salandra, 1923 LNOJ 663.

[7] ibid.

[8] ibid.

[9] n. 5, p. 12.

[10] ibid, p. 14.

[11] ibid, p. 27.

[12] ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid, p. 28.

[16] ibid, pp. 28-29.

[17] Spiermann, O., 2005. International legal argument in the Permanent Court of International Justice: The rise of the international judiciary. Cambridge University Press, p 167.

[18] Moore ‘Suggestions for consideration, as to the Clauses to Follow the First Two Paragraphs (of the Recitals) of the Draft of Resolution’, undated, Moore Papers 172, as cited by Spiermann, n. 17., p. 169.

[19] Annex 576a C, 1923 LNOJ 1501, p. 1502

[20] Moore to Huber 18 September 1926 Huber papers 24.1, Moore papers 172, as cited by Spiermann, n. 17, p. 169.

[21] n. 19.

[22] Letter from the Secretary of State of the United States of America to the Secretary-General of the League. Washington, 2 March 1926, Minutes of the Conference of the States Signatories of the Protocol of Signature of the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice, Annex 2, p. 68.

[23] Final Act, Minutes of the Conference of the States Signatories of the Protocol of Signature of the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice, Annex 7, p. 78.

[24] Pomerance, M., 1973. The Advisory Function of the International Court in the League and UN eras. Johns Hopkins University Press.

[25] The phrase was employed by Fitzmaurice. Interpretation of Peace Treaties, Written Statements, p. 305.

[26] Interpretation of Peace Treaties, 1950 ICJ Reports 65, p. 71.

[27] ibid (emphasis added).

[28] ibid.

[29] ibid.

[30] ibid (emphasis added).

[31] This distinction was already advanced by the Court in Interpretation of Article 3‚ Paragraph 2‚ of the Treaty of Lausanne, PCIJ Series B, No. 14. However, this distinction was circumvented by the ICJ in Western Sahara, 1975 ICJ Reports 12.

[32] Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, 2004 ICJ Reports 136, p. 157, para 46.

[33] ibid, pp. 157-58, para 47.

[34] ibid, p. 159, para 49.

[35] ibid.

[36] ibid, p. 159, para 50 (emphasis added).

[37] ibid, p. 163, para 62; cf Separate opinion of Judge Kooijmans, pp. 226-227, esp. paras. 25 and 27

[38] ibid

[39] A/71/PV.88, p. 6.

[40] ibid, p. 7.

[41] ibid, p. 8.

[42] ibid, p. 11.

[43] Ibid.

[44] ibid, p. 13.

[45] n. 27, p. 71.