ESIL Reflection – The Rise of Nonviolent Protest Movements and the African Union’s Legal Framework

PDF Version

Vol 10, Issue 4

Editorial board: Federico Casolari, Patrycja Grzebyk, Ellen Hey, Guy Sinclair and Ramses Wessel (editor-in-chief)

Florian Kriener (Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public and International Law) and Elizabeth A. Wilson (Rutgers Law School)

The Rise of Nonviolent Protest Movements and the African Union’s Legal Framework

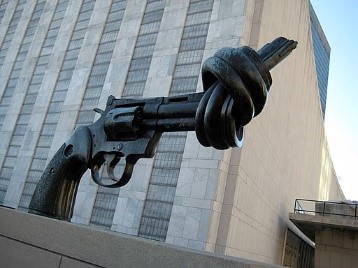

A defining political phenomenon of the last century has been the rise of mass nonviolent civil resistance movements as a vehicle for change. Defined as “a civilian-based method used to wage conflict through social, psychological, economic, and political means without the threat or use of violence,”[1] nonviolent civil resistance movements arguably have become “the model category of contentious action worldwide.”[2] From 1900 to 2019, researchers have identified a total of 325 large-scale nonviolent campaigns with “maximalist” aims such as forcing incumbent governmental leaders from power, gaining independence, or causing the withdrawal of foreign occupiers.[3] Smaller-scale campaigns with agendas aimed at domestic reforms number thousands or hundreds of thousands more.[4]

Not only are nonviolent resistance movements growing in frequency but they are also demonstrating their effectiveness as an alternative to violence. Groundbreaking research by political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan has shown that large-scale nonviolent resistance movements are over twice as effective (53% versus 26%) as violent movements in achieving their goals. Moreover, research shows that nonviolent revolutions are the most important driver for democratic transitions in authoritarian environments, resulting in enduring democracies two and a half times more often than violent revolutions (74% versus 29%).[5]

Heretofore, international law has viewed such movements mainly through the lens of human rights law. Individual and group participants in civil resistance movements are rights-holders and thus beneficiaries of human rights treaties. The Human Rights Committee recently published its General Comment 37 on the right of peaceful assembly, which highlights the importance of protests for the fulfillment of human rights in a democratic society. [6] Alongside the rights to peaceful assembly and association, numerous other rights protect and enable protests.

However, given the significant impacts that such movements are having on the shape of the international order, the rise of nonviolent protest movements raises a multitude of further general questions for international law — questions regarding, inter alia, the laws of war, sources of law, the locus of sovereignty, the principle of non-intervention, and the status of a right to democracy. This Reflection focuses on one of these general questions: the role of protest movements in the recognition of governments.

Traditionally, international law has been agnostic towards nonviolent protest movements demanding change in their domestic spheres. Because of the customary international law doctrine of “effective control”, a government merely has to demonstrate its ability to exact habitual obedience in order to be recognized by the international community as the actual (and thus lawful) representative of the population. This doctrine means that a revolution – nonviolent or not – only has legal significance if it succeeds in creating a new government.[7] Otherwise, a movement seeking the ouster of a government is – from the perspective of international law – of no relevance.

Yet today states frequently engage with nonviolent movements in foreign states: they issue statements of solidarity with protesters, sanction states that violently repress nonviolent movements, support protest movements financially, and welcome protest leaders in their capitals. Sometimes, states recognize governments that assume power through a peaceful revolution or derecognize a government faced with widespread protests.[8]

In this regard, the suspension practice of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) of the African Union (AU) points toward an emerging regional norm that awards recognition to governments that come to power through nonviolent revolutions, despite the prohibition of “unconstitutional changes of government” in the African Union’s regional framework. This emerging regional norm has the potential to become a model guiding the incorporation of protest movements in general international law. It thus merits further scrutiny.

Democracy in the Law of the African Union

The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG), signed in 2007 and entered into force in 2012, establishes the democratic principle in the AU’s normative framework and provides procedures for the promotion of democracy. Tasked with the multilateral enforcement of democracy amongst the AU’s member states, the PSC may suspend governments that accede to power in an unconstitutional manner and may sanction the perpetrators of unconstitutional changes in government (Art. 25 ACDEG). With this framework, the AU makes recognition of governments contingent on democratic transitions. It thus rejects the doctrine of “effective control.” The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACPHR) likewise protects and enables peaceful assemblies and protest (Arts. 10, 11). Moreover, Article 20(2) ACPHR grants “colonized or oppressed peoples” a right to “free themselves from the bonds of domination” through lawful means, which some consider to legitimize pro-democratic protests against undemocratic governments.[9]

Nonviolent movements are of increasing relevance to the African Union. Recourse to nonviolent protests occurs with particular frequency in repressive environments, where institutional participation mechanisms such as elections and constitutional procedures are effectively barred for the public. Where constitutional means of change are closed off, popular protests may be the only route for “the people” to voice their opinion and demand change. This is particularly true in Africa where 28 of 54 member states had authoritarian governments as of 2020.[10] From 2009-2019, one-third of all the revolutionary mass nonviolent protests in the world have occurred in Africa – 25 in all, in countries ranging from Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar and Mali to South Africa, Tunisia, Zambia, Algeria and Sudan. Almost twice as many nonviolent movements occurred in Africa as in Asia, the next most active region with 16. Moreover, since the 1970s, nonviolent movements in Africa have been more successful than in the rest of the world in achieving governmental change.[11] In that time, roughly 58% of movements have succeeded in ending autocratic regimes, compared to a 44% success rate in the rest of the world.[12] In order to achieve the democratic ambitions of the ACDEG, support for nonviolent revolutions can therefore be necessary.

Nonviolent movements and the prohibition of unconstitutional change in government

However, nonviolent revolutions sit uneasily within the AU’s normative framework. Revolutions, even nonviolent ones, function outside of the institutional democratic processes guaranteed by Articles 17 of the ACDEG (reaffirming the commitment of states “to regularly holding transparent, free and fair elections”) et seq.

The ACDEG is silent on the question of whether transitions effected by nonviolent mass protests are included within the definition of an unconstitutional change of government.[13] Art. 23 ACDEG lists five forms of prohibited unconstitutional change in government, which do not include nonviolent revolutions. While the five modalities are only listed as examples of an unconstitutional change in government,[14] the general rule remains that governments have to ascend to power through a constitutional mechanism. The situation is further complicated when military intervention occurs alongside popular protests.

Recognizing the “lacuna” in the ACDEG,[15] the PSC in 2014 called on the AU Commission to review relevant normative frameworks in order to develop a consolidated AU draft framework, including “appropriate refinement of the definition of unconstitutional changes of government, in light of…popular uprisings against oppressive systems.”[16] The PSC revisited the topic in an August 2019 “brainstorming session” and reiterated its call for the draft framework,[17] but as of September 2021 no report has been released.

Still, against the backdrop of this normative uncertainty, the PSC has developed a practice that accepts nonviolent revolutions as in accordance with the ACDEG under two circumstances. First, when mass protests lead to the resignation of a government without military intervention. Second, when a military intervention responds to widespread popular protests demanding the removal of the government and the military commits to a specific timeline for transition to civilian rule. If the military does not transition to civilian rule within a short time span, the PSC will consider the military intervention an unconstitutional change in government and will suspend the state party. This conclusion is based on the analysis of the eight cases in which the PSC dealt with nonviolent revolutions.

Tunisia, Egypt, Burkina Faso

The PSC was first confronted with the question of nonviolent revolution after the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia. Faced with widespread popular protests, long-standing President Ben Ali fled the country in January 2011. Shortly afterwards, the Tunisian Constitutional Court named the speaker of the national assembly interim leader.[18] Instead of suspending Tunisia for this extraordinary change in government, the PSC welcomed the developments in its Press Statement on the Tunisian situation.[19]

The second nonviolent revolution of the Arab Spring in Egypt in 2011 likewise saw an abrupt departure of President Mubarak from power. This time, however, he was removed by military forces that formed a transitional government and suspended the constitution. Though the core leaders of the revolution were unhappy with the military’s power grab and tried to negotiate with the military,[20] many protesters applauded the military for its role in upending the 29-year-long dictatorship. Faced with these circumstances, the PSC did not suspend Egypt from its participation in the AU, despite the unconstitutional change of government.[21] In its communique on Egypt, the PSC called the situation “exceptional,” noting both the people’s “desire for democracy” and the pro-democratic measures the military interim government was taking, which included writing a constitution. The PSC conditioned its position on a rapid transition to civilian power and free and fair elections, which were held in 2012.

President Morsi, the winner of those elections, was then confronted with popular uprisings only one year later. In July 2013, the military – again – intervened and deposed Morsi. However, the new military government was promptly suspended by the PSC because the military had not credibly promised a quick handover to civilian power, even though popular protest accompanied the transition.[22]

In 2014, Burkina Faso’s military intervened against President Blaise Compaoré against a backdrop of popular protests. But protestors worked closely with the interim military government to transition governmental authority to a civilian-led body, and fresh elections were organized in 2015. The PSC did not suspend Burkina Faso and only condemned the military government as a coup d’état, giving it a two-week deadline to restore the civilian power, with which the military complied. At the same time, the PSC praised the “profound aspiration” of the people of Burkina Faso “to uphold their Constitution and to deepen democracy in the country.” [23]

Consolidating the practice: Sudan, Algeria, Mali, Guinea

With one exception, the most recent cases confirm this emerging norm.

The exception is the military deposition of Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe in 2017. The widespread protests before the military intervention against his government were initially considered a legitimizing factor for the interim military government. However, the military has not followed up on its promise to organize free and fair elections and to transition to civilian power.[24] The PSC should have suspended Zimbabwe after noting the military government’s limited will to enact democratic reforms and transition to civilian rule but has not done so. Accordingly, the PSC received heavy criticism for omitting suspension.[25]

But after Zimbabwe, the PSC resumed the pattern of recognition we have described here. The resignation of President Bouteflika in Algeria amidst widespread nonviolent protests in early 2019 did not prompt Algeria’s suspension[26] since, when the military assumed power, it announced fresh elections to be held later in 2019.[27] Likewise, the military coup in Mali in August 2020 provoked Mali’s suspension, despite some nonviolent protests against ousted President Keita’s government.[28] The Malian military had not credibly assured the PSC of a civilian-led transition to fresh elections in conformity with the protesters’ demands. The PSC likewise threatened sanctions against the leading figures of the Malian coup d’état.[29]

The PSC’s engagement with Sudan in 2019 is particularly salient for the emerging norm of recognition based on nonviolent protest movements. Protests erupted in late 2018 and gained traction throughout early 2019. On April 11th, the Sudanese Armed Forces deposed long-term President Omar Al-Bashir and established a Transitional Military Council (TMC). A few days later, the PSC acknowledged the change in government as an unconstitutional change in government but did not suspend the Sudanese government.[30] It rather set a deadline for a transition to civilian government, which it went on to extend in late April. During April and May, the representatives of the protest movement negotiated with the TMC on a transitional period. Talks however broke down in late May and, in early June, the TMC cracked down on the central protest camp in Khartoum, leaving over 100 protesters dead. The protest movement withdrew from the talks and withdrew its support for the TMC.[31] Without the protesters’ support, the TMC could not claim sufficient legitimacy.[32] The PSC therefore suspended Sudan on June 6th.[33] Its government was readmitted to the AU when a constitutional agreement was reached and a civilian-led transitional government was sworn into office in late August 2019.[34]

In 2021, the PSC suspended two coup governments that had taken power without significant support from a non-violent protest movement, thus confirming the outlined practice.[35] Both in Mali and Guinea, military officials deposed their respective governments without pledging to transition to democracy in a short timeframe.

In summary, the PSC’s practice is establishing a framework for assessing nonviolent protest movements. By not suspending states where a nonviolent, if unconstitutional, change of government has occurred, the PSC endorses – at least to some extent – nonviolent protest movements if they struggle for the deposition of a long-standing autocrat and recognizes nonviolent revolutions as a form of democratic transition. In the case of nonviolent revolutions, the PSC is creating an exception to the prohibition on unconstitutional changes of governments. This exception is based on the democratic principles enshrined in the AU’s treaties. The new framework has implications for the Law of the AU and beyond.

Implications for the Regional International Law of the African Union and for General International Law

With respect to the regional international law of the African Union, the suspension practice of the PSC shows that the democratic norm in the AU encompasses a more substantive meaning than just the holding of frequent elections. Additionally, elections must be free and fair and require a true competition among the competing voices in society. If elections do not offer such a choice, as is the case in a variety of authoritarian and semi-authoritarian states, a true government of the people can only find expression in popular – democratic – protests. By accepting democratic revolutions within its democracy framework, the AU thus attaches itself to a deeper understanding of democracy.

With respect to international law more generally, the AU practice described here has implications for the question of how to incorporate nonviolent protest movements into general international law.[36] The AU’s model provides a template for states to engage with and recognize or derecognize revolutionary governments and governments faced with protests. Elements thereof can already be seen with regard to the recognition of Juan Guaidó’s interim government in Venezuela[37] and the derecognition of Alexander Lukashenka’s government in Belarus.[38] In both cases, the presence of nonviolent movements was a decisive factor for states to decide upon their recognition policies.

Moreover, international organizations and non-African states tend to follow the decisions of the PSC when engaging with situations in Africa. This was particularly salient in the case of Sudan.[39] During the Security Council debates, almost all states affirmed that they would act in conformity with the PSC’s decisions on Sudan. Its decision to suspend Sudan was widely applauded[40] and, in this spirit, the EU decided to withhold recognition from the Transitional Military Council.[41] By shaping other states’ (legal) foreign policies towards African situations, the AU is thus exercising normative power that has influence on the general development of international law in the field. As a significant number of nonviolent protest movements occur in Africa, the AU’s normative impact is set to grow.

In conclusion, therefore, the normative developments concerning the role of nonviolent protest movements in the AU’s legal framework will have a significant impact on the development of general international law in the upcoming years. By accepting democratic revolutions in certain circumstances, it provides a framework for states and international organizations to engage with nonviolent revolutionary movements, which could foster democratic developments worldwide. It is a template for how international law can accompany the rising importance of protest movements in the international domain, which will continue in coming years.

Cite as:

Florian Kriener and Elizabeth A. Wilson, ‘The Rise of Nonviolent Protest Movements and the African Union’s Legal Framework’, ESIL Reflections 10:4 (2021).

* Florian Kriener is a Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public and International Law in Heidelberg, Germany. Elizabeth A. Wilson is a Visiting Research Scholar at Rutgers Law School, in Camden, N.J., United States.

[1] Erica Chenoweth & Maria J. Stephan, “Why Civil Resistance Works,” International Security, Vol. 33(1) (2008): 9.

[2] Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, “How the World is Proving Martin Luther King Right about Nonviolence,” Washington Post: Monkey Cage (January 18, 2016), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/01/18/how-the-world-is-proving-mlk-right-about-nonviolence/.

[3] Erica Chenoweth, “The Future of Nonviolent Resistance,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 31(3) (2020): 69-70.

[4] Erica Chenoweth, “The Future of Nonviolent Resistance,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 31(3) (2020): 71.

[5] Jonathan C. Pinckney, From Dissent to Democracy, The Promise and Perils of Civil Resistance Transitions, OUP, Oxford 2020.

[6] Human Rights Committee, General Comment 37, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/GC/37. For an overview of the positive human rights law related to nonviolent civil resistance, see Elizabeth A. Wilson, People Power Movements and International Human Rights: Creating a Legal Framework (International Center for Nonviolent Conflict, 2019), pp. 64-76. https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/resource/people-power-movements-international-human-rights-creating-legal-framework/

[7] Hans Kelsen, General Theory of Law and State, Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1949, 118.

[8] Erica Chenoweth & Maria J. Stephan, The Role of External Support in Nonviolent Campaigns, Poisoned Chalice or Holy Grail?, ICNC Monograph Series, Washington D.C. 2021.

[9] Pacifique Manirakiza, “Towards a Right to Resist Gross Undemocratic Practices in Africa”, Journal of African Law 63 (2019).

[10] Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2020, In sickness and in health?, 2021, https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/)

[11] Zoe Marks, Erica Chenoweth & Jide Okeke, “People Power Is Rising in Africa: How Protest Movements Are Succeeding Where Even Global Arrest Warrants Can’t,” Foreign Affairs (25.04.2019).

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/africa/2019-04-25/people-power-rising-africa.

[12] Ibid.

[13] See Solomon A. Dersso, The Status and Legitimacy of Popular Uprisings in the AU Norms on Democracy and Constitutional Governance, Journal of African Law, 63, S1, 2019, 107; Florian Kriener, Gewaltfreie Protestbewegungen als Legitimitätsquelle? Eine Replik, ZaöRV, 80, 4, 2020, 881, 886-887.

[14] Art. 23 ACDEG lists the five modalities of unconstitutional regime change as “inter alia” examples, which hint at a non-conclusive elaboration.

[15] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 432nd Meeting (29.04.2014), PSC/PR/BR.(CDXXXII0).

[16] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 432nd Meeting (29.04.2014), PSC/PR/BR.(CDXXXII0), at 3.

[17] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 871st Meeting (22.08.2019), PSC/PR/BR (DCCCLXXI).

[18] AU Recognizes Tunisia’s Speaker as Interim Leader, Voice of America, 14.01.2011, abrufbar unter: https://www.voanews.com/a/au-recognizes-tunisias-speaker-as-interim-leader-113778229/133592.html (zuletzt abgerufen am 24.03.2011).

[19] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 268th Meeting (23.03.2011), PSC/PR/BR.2(CCLXVIII).

[20] McGreal, Army and protesters disagree over Egypt’s path to democracy, The Guardian, 12.02.2011, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/feb/12/egypt-military-leaders-fall-out-protesters.

[21] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 260th Meeting (16.01.2011), PSC/PR/COMM.(CCLX).

[22] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 384th Meeting (05.07.2013), PSC/PR/COMM.(CCCLXXIV).

[23] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 465th Meeting (03.11.2014), PSC/PR/COMM.(CDLXV).

[24] See Hoitismolimo Mutlokwa, “A Failed State in the Making: How Zimbabwe’s Constitutional Amendment bill No.2, 2019 constrains judicial independence”, 07.05.2021, https://verfassungsblog.de/a-failed-state-in-the-making/.

[25] Philip Roessler, How the African Union got it wrong on Zimbabwe, Al-Jazeera, 05.12.2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/african-union-wrong-zimbabwe-171204125847859.html.

[26] PSC Report, From popular uprisings to regime change, Institute for Security Studies, 21.08.2019, https://issafrica.org/pscreport/psc-insights/from-popular-uprisings-to-regime-change.

[27] The elections took place in December 2019, but were boycotted by a significant portion of the Hirak Protest Movement, see: Joseph Hincks, “Why Protesters Are Boycotting Algeria’s Elections Today”, Time Magazine, 12.12.2019, https://time.com/5748726/algeria-elections-boycott/.

[28] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 941st meeting (19.08.2020), PSC/PR/COMM.(CMXLI).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 840th Meeting (15.04.2019), PSC/PR/COMM.(DCCCXL).

[31] Sudanese Professionals Association, Press Release: Escalating the Revolution and Terminating Negotiations with the Coup Council, 03.06.2019, https://www.sudaneseprofessionals.org/en/press-release-escalating-the-revolution-and-terminating-negotiations-with-the-coup-council/.

[32] Florian Kriener, Nonviolent Movements and the Recognition of Governments: What Implications for International Law?, Minds of the Movement Blog, 02.03.2021, https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/contributor/florian-kriener/.

[33] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 854th Meeting (06.06.2019), PSC/PR/COMM.(DCCCXLIV).

[34] Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 875th Meeting (06.09.2019), PSC/PR/COMM.(DCCCLXXV).

[35] Suspending Mali: Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 1001st Meeting (01.06.2021), PSC/PR/COMM.(1001(2021) and Guinea: Peace and Security Council, Press Statement, 1030th Meeting (10.09.2021), PSC/PR/COMM.(1030(2021).

[36] Elizabeth A. Wilson, “‘People Power’ and the Problem of Sovereignty in International Law”, 26 Duke J. Comp. & Internat’l Law 201 (2016).

[37] Florian Kriener, Gewaltfreie Protestbewegungen als Legitimitätsquelle? Eine Replik, ZaöRV, 2020.

[38] Florian Kriener, Nonviolent Movements and the Recognition of Governments: What Implications for International Law?, Minds of the Movement Blog, 02.03.2021.

[39] United Nations Security Council, 8513th meeting, S/PV.8513, 17.04.2019.

[40] United Nations Security Council, 8549th meeting, S/PV.8549, 14.06.2019.

[41] European Council, Declaration by the High Representative, Federica Mogherini, on behalf of the European Union on Sudan, 17.04.2019, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/04/17/declaration-by-the-high-representative-federica-mogherini-on-behalf-of-the-european-union-on-sudan/.

© 2021. This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence.